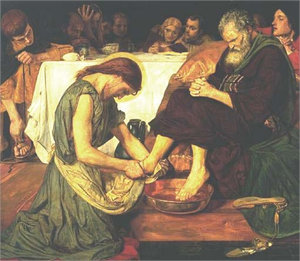

The Johannine Footwashing and the Death of Jesus

The Johannine Footwashing and the Death of Jesus

David Gibson

Introduction

‘The properly Johannine theology of salvation does not consider the death of Jesus to be a vicarious and expiatory sacrifice for sin’.[1] This position, defended by Forestell in 1974, arguably still expresses a broad critical consensus on the interpretation of the cross in the Fourth Gospel. Our aim in this article is to engage with this position by providing a detailed study of John 13:1-11, a passage which, we suggest, contributes significant but often over-looked exegetical material to John’s portrayal of the death of Jesus. These exegetical issues will attempt to engage with the critical dialogue between methodological and theological questions. We will briefly outline some of the main scholarly viewpoints on the cross in John’s Gospel, and seek to provide an initial critique of some of these formulations. In this way our paper has the two-fold aim of seeking to raise questions about a dominant methodology used to interpret the cross, and to provide an exegetical study which may contribute to the debate over whether John attaches a theology of salvation to the cross that is not cast exclusively in terms of revelation and glorification.

Content and method in dominant formulations of the death of Jesus in John

The work of Rudolf Bultmann, although extensively modified in different ways by later scholarship, has arguably set the tone for much of the critical consensus on our topic. Bultmann argued that ‘In John, Jesus’ death has no pre-eminent importance for salvation, but is the accomplishment of the “work” which began with the incarnation.’[2] This reference to the incarnation is instructive in that, for Bultmann, the incarnation is the decisive act of God, both in terms of salvation and revelation; indeed, it is correct to say that revelation is salvation. J. T. Forestell has provided a significant development of Bultmann’s thesis in his argument that the death of Jesus does not merely complete this revelation but is actually central to it as the climactic expression of God’s love.[3] At his death Jesus supremely reveals the glory of God and through this is able to draw his followers into communion with himself and the Father. This revelation ‘can be considered to be salvific without the necessity of evaluating the cross in terms of a cultic sacrifice or of moral satisfaction for sin’.[4] The importance of Christology in interpreting the cross in John is given its sharpest focus in Ernst Käsemann’s study of John 17. For him the cross must be viewed in the light of John’s ‘naïve docetism’ which presents Jesus as God striding on the earth; he is tempted to regard the passion narrative as ‘a mere postscript which had to be included because John could not ignore this tradition nor yet could he fit it organically into his work’.[5] Although Käsemann does view the cross as a ‘manifestation of divine self-giving love’, the stress falls heavily on Jesus’ death as his ‘going away’ to the Father in ‘a victorious return from the alien realm below’.[6] G. Nicholson is critical of the way in which Käsemann seeks to integrate the cross and Christology, but nevertheless locates his own work along the same trajectory. He presents Jesus’ death as fundamentally a ‘departure’ to glory which can only be understood in the light of the Johannine ‘descent-ascent schema’.[7]

These formulations of the death of Jesus vary significantly and contain within themselves different methodological assumptions; however, they share a common antipathy to seeing any kind of ‘atonement’ theology in John, coupled with a prioritisation of Christology as the vital hermeneutical lens for viewing the cross. This emphasis on Christology as the all-determining starting point may, however, actually blur the lens by restricting its focus, and closer examination of some of the above views reveals some methodological problems. For instance, Nicholson’s thesis is built on a study of the three hypsoo sayings (3:14; 8:28; 12:32ff). His approach excludes other texts such as the hyper sayings (6:51; 10:11, 15; 11:50, 51, 52; 15:13; 17:19; 18:14) and he justifies this exclusion by stating that while ‘there is an outcropping of such language in the Fourth Gospel, the Gospel itself is not determined by categories of sacrifice and atonement’.[8] This approach is problematic on at least two counts. First, ‘outcropping’ is hardly an adequate term to describe the hyper sayings when at the purely statistical level they are more prevalent than the hypsoo sayings. Second, it creates a false antithesis for one does not have to hold that the Gospel is determined by categories of sacrifice and atonement to hold that it at least contains these categories. Nicholson’s method means the evaluation of exegetical particulars in the light of a pre-determined Christological framework.

Some formulations of the death of Jesus share a common antipathy to seeing any kind of ‘atonement’ theology in John.

It is not clear how an overall account of the death of Jesus can be confidently asserted on the basis of a selective approach to the exegetical aspect of the problem;[9] and the same holds true for the theological aspect. Nicholson himself rightly questions whether Forestell provides a truly comprehensive presentation, for to hold that the cross saves the believer in a revelatory sense does not answer the important theological question of what it saves the believer from or for?[10] The criticisms of D. A. Carson seem to carry weight when he suggests that the views of Forestell, Käsemann and Nicholson operate with a ‘tyranny of the dominant theme’ – Christology is elevated to the level of a controlling matrix against which everything else in the Gospel must be set and this approach inevitably drowns out the ‘minor chords’.[11] It can be argued that a broader methodology for interpreting the death of Jesus needs to be adopted, one which encourages a dialogue between Christological and soteriological concerns without allowing one to dictate the other. We will attempt to cast the exegetical net slightly wider than is often the case by examining John 13:1-11 in detail. Our study will examine the significance of chapter 13 in its context and the way this context both informs, and is informed by, the structure of the opening three verses. We will then move on to consider other exegetical issues in these verses which may provide at least some minor chords in John’s interpretation of the cross.

The context of chapter 13 and the structure of vv.1-3

All commentators observe how vv.1-3 of this chapter are laden with theological significance and their tight syntactical construction means that they deserve to be treated together. Following Bultmann and Boismard, some scholars view them as the first ‘overloaded’ indicators of at least two disparate sources underlying the whole chapter.[12] Our study proceeds on the basis that, whatever its compositional history, John 13 offers a coherent narrative as it now stands and that to view vv.1-3 as overloaded runs the risk of misconstruing their function in the Gospel.[13] More satisfactory is W. Grossouw’s observation that the verses function as a kind of ‘minor prologue’ to the second half of the Gospel by introducing its principle themes: love; Jesus’ going away to the Father; the power of granting life by dying; Jesus’ foreknowledge and control in going to his death; and the work of the devil and his instrument.[14]

This tight concentration of themes both introduces a new section in the Gospel and makes a number of connections with other parts of the Gospel which inform its context. The opening words ‘Now before the Feast of the Passover’ (pro de tes heortes tou pascha), tie the section to what has gone before, both immediately (11:55; 12:1) and earlier (2:13, 23; 6:4), as well as to what will follow (18:28, 39; 19:14). The Passover references in 11:55 and 12:1 form part of the context for the events (12:20-22) which increase the concentration on Jesus’ impending death (12:23). Schnackenburg highlights the role that the Passover theme plays in the gradual progress towards the cross: ‘in 11:55 it is “drawing near”; the anointing at Bethany took place “six days before” (12:1); the farewell meal takes place “before the passover”; and the day of condemnation and execution is the “day of rest” of the passover (19:14)’.[15]

It is beyond our scope to examine the chronological and theological issues in John’s treatment of the Passover; here we simply note that it acts as a pointer towards Jesus’ death understood as his ‘hour’ (hora). This word forges connections to earlier references (2:4; 7:8, 30; 8:20) with the distinction that from 12:23 onwards the ‘hour’ has now arrived. It contributes to many of the dominant interpretations of Jesus’ death as in 12:23, 27-33 it connects the theme of glory with death, and in 13:1 it appears in the participial phrase ‘Jesus, knowing that his hour had come to depart out of this world to the Father’ (eidos ho Iesous hoti elthen autou he hora hina metabe ek tou kosmou toutou pros ton patera). In this way the meaning of Jesus’ ‘hour’ is drawn from the context in which the term appears; we will suggest that when its context in v.1 is combined with a very similar phrase in v.3, the result is the emergence of another dimension to the cross alongside the glory-departure motifs.

The second participial phrase in v.1 is extremely significant: ‘having loved his own who were in the world, he loved them to the end’ (agapesas tous idious tous en to kosmo eis telos egapesen autous). Many scholars point out that eis telos is capable of both an adverbial (‘to the uttermost’) and a temporal (‘to the end’) meaning, with most suggesting that in customary Johannine fashion both are probably intended.[16] The temporal sense connects strongly with the sense of Jesus’ hour which has now arrived. Schnackenburg builds on this to argue that the aorist participle agapesas refers to the relationship between Jesus and his disciples up to this point, whereas the finite verb egapesen must point to a single action on Jesus part; combined with the temporal sense of eis telos and the reference to Jesus’ hora, he argues that the referent must be the cross.[17] However, this presentation of a single action on Jesus’ part as an act of love must be considered in the light of the way in which vv.1-3 are structured.

H. Ridderbos argues that 13:1-3 provides a ‘double introduction’ to the farewell discourse with two parallel sentences which perform different functions.[18] The two parallel participial clauses (v.1 eidos ho Iesous hoti and v3. eidos hoti) are separated by the reference to the supper taking place, and for this reason Ridderbos argues that the import of v.1 is broader than that of vv.2f.: the first sentence relates to the whole of ‘Jesus’ suffering and death, which is about to be described, while “Jesus, knowing …” in vs.3 relates especially to the last meal, referring to it as a symbolic overture to and anticipation of the chain of events announced in vs.1’.[19]

Functioning as the introductory text for the farewell discourse, then, v.1 colours all of Jesus’ actions and words from this point onwards and means that they will function as demonstrations of his love. In this way Schnackenburg suggests that egapesen refers primarily to Jesus’ death on the cross without excluding a secondary symbolic reference in the washing of the disciples’ feet.[20] The fact that in v.3 the reference to Jesus ‘knowing that the Father had given all things into his hands and that he had come from God and was going to God’ (eidos hoti panta edoken auto ho pater eis tas cheiras kai hoti apo theou exelthen kai pros ton theon hypagei) is followed immediately by an act of humble service, arguably suggests that in this particular context Jesus’ supreme authority and departure to God are both qualified by self-abasing love. Here Ridderbos charges Käsemann with a one-sided presentation of the concept of glory and argues that if the footwashing is taken to be a symbolic overture to the cross, then soteriology is joined with Christology.[21] Similarly Barrett comments on v.3: ‘Jesus was going to his eternal glory with the Father through the humiliation of the cross, of which the footwashing was an intended prefigurement’.[22] We now turn to consider other issues in 13:1-11 which bear on the interpretation of Jesus’ death.

Further exegetical and theological details in 13:1-11

Verses 2-4 contribute some individual notes to John 13’s minor chord. J. C. Thomas argues that ‘supper’ (deipnon) in v.2 evokes the account of another meal in 12:1-8. This contains parallels to 13:1-11 in its references to Judas and the anointing of feet in association with death. He further suggests that with the use of ‘towel’ (lention) in v. 4 Jesus is attired as a servant and consciously foreshadowing the humiliation he will undergo at the cross.[23] In this regard, some scholars also see symbolic significance in the laying aside of outer garments (tithemi) and taking up (lambano) the towel. R. B. Edwards argues that both words are unusual as terminology for removing and resuming clothing; she joins Brown and Barrett in suggesting that the terms probably echo Jesus’ earlier references to laying down his life and taking it up again (10:11, 15, 17-18).[24] Combined with the mention of Jesus’ betrayer and the diabolos, a murderer from the beginning (8:44), these details serve to locate the unfolding narrative in the hour of Jesus’ death.

Peter’s objection to the footwashing in vv.5-6 prepares the way for the key theological explanations of the event. In v.7 Jesus responds to Peter’s negative reaction: ‘what I am doing you do not understand now, but you will understand after these things’ (ho ego poio sy ouk oidas arti gnose de meta tauta). The use of meta tauta makes a clear connection to a recurring Johnannine distinction between the understanding of the disciples before Jesus’ death and resurrection and that which they possess retrospectively (cf. 2:22; 8:28; 12:16; 13:19; 14:29; 20:9). If the death and resurrection of Jesus can be understood as the events which lead to the gift of the Spirit who will testify to the truth about Jesus (7:37-39; 14:26; 15:26; 16:13),[25] then texts like 13:7 would seem to suggest that a nexus of events lying ahead will provide the proper understanding of Jesus’ words and actions. Jesus’ death clarifies the revelation of his identity.[26] This provides an important qualification to Nicholson’s acceptance of M. Appold’s thesis that Jesus’ identity interprets the cross,[27] for there is clearly a sense here in which the cross interprets Jesus or, at the very least, his actions. The narrative progresses on the basis that the true meaning of what is taking place has yet to become clear and this further encourages a symbolic understanding of the footwashing.

Peter, however, ignores the promise of future understanding. In v.8 he makes an emphatic rejection of Jesus’ action (ou me with the future indicative, coupled with eis ton aiona). Thomas points out how the only other passages in John which contain the formula ou me + aorist subjunctive/future indicative + eis ton aiona come from Jesus concerning eternal life. He observes: ‘In a twist as ironic as Caiaphas’s prophecy, Peter uses the very formula Jesus has used to offer life to refuse Jesus’ offer’.[28] In his response, Jesus makes it clear to Peter that the footwashing is not optional and has far-reaching consequences:[29] ‘unless I wash you, you do not have a share with me’ (ean me nipso se, ouk echeis meros met emou). We will come to look at the significance of ‘wash’ (nipto) in our discussion of v.10; here we note the importance of having a ‘share’ or ‘part’ (meros) with Jesus. In the LXX the word is used with respect to Israelite inheritance in the promised land (Numbers 18:20; Deuteronomy 12:12; 14:27) and this sense appears to have been developed so that it came to refer to participation in eschatological blessings.[30] If there is an eschatological sense in v.8 then importantly it is tied to the ‘with me’ (met emou) and it is right to ask what blessings Jesus bestows on his followers. Commentators note how having a meros with Jesus is given some content in 12:26; 14:1-3, 19, 21-23, 17:22, 24 with the main emphasis being that his followers will be able to share in his glory and life.[31]

This connects with at least two issues in our argument. First, it is clear that having a ‘part’ with Jesus depends directly on the washing; it is the symbol of a necessary action by Jesus. As Brown states succinctly: ‘the footwashing is something which makes it possible for the disciples to have eternal life with Jesus. Such emphasis is intelligible if we understand the footwashing as a symbol for Jesus’ salvific death’.[32] Second, this in turn challenges views which hold that Jesus’ death affects no change either in his relationship to his followers, or in God’s relationship to the world. As Thompson argues, Käsemann’s thesis that Jesus’ death is simply his return to the Father cannot be substantiated here since, if a symbolic reference is granted to the footwashing, 13:8 suggests that Jesus’ death effects a necessary change in his relationship with ‘his own’.[33]

If a symbolic reference is granted to the footwashing, it suggests that Jesus’ death effects a necessary change in his relationship with ‘his own'.

This leads us to consider nipto and its repetition in v.10 where it is accompanied by ‘bathe’ (louo). The issue of whether there is any distinction between nipto and louo is complicated by the thorny problem of v.10’s textual variant, and it is on the basis of the text-critical decision that commentators divide into sacramental and non-sacramental readings. As Thomas notes ‘the decision to include or omit ei me tous podas [‘except the feet’] affects the interpretation of the entire passage’.[34] The omission of the phrase lends weight to the thesis that the footwashing is symbolic of Jesus’ death without a sacramental reference. The reading ‘The one who has bathed does not need to wash’ (ho leloumenos ouk echei chreian nipsasthai) allows the interpreter to see the footwashing as symbolic of the leloumenos and not an additional cleansing. Dunn explains: ‘the loueiv refers to the niptein of v.8 while the niptein of v.10 refers to the further washing requested by Peter in v.9. V.10 is the answer to this request: ho leloumenos is the person who has received the footwashing’.[35] If the longer reading is taken, this appears to relegate the footwashing to being something other than a complete ‘bath’, and as such forces more of a distinction between louo and nipto. Here the former term is then usually held to point towards baptism and the latter to forgiveness of post-baptismal sins.[36]

We follow Thomas who shows the textual evidence in favour of the longer (and more difficult) reading,[37] but suggest that this does not have to force an acute distinction between louo and nipto. Carson comments that a distinction is not often maintained by Greek writers and notes John’s fondness for synonyms.[38] He traces the narrative dialogue to argue that although the footwashing in vv.6-8 symbolises the cleansing provided by the cross, Peter’s exuberance in v.9 sees Jesus turn the footwashing to a different application in v.10: the initial cleansing provided by Jesus is a once-for-all act.[39] On this basis louo refers to the initial cleansing while nipto, in reference to feet, refers to the ongoing experience of needing to have subsequent sins washed away. If it is objected that the longer reading prevents the footwashing from referring to the once-for-all cleansing, Carson points out that this is beside the point: ‘In this verse [v.10] that may be so - but the point is that this verse has launched into a new application of the footwashing’.[40] This view can sit comfortably with coherent explanations of the entire narrative (even those based on the shorter reading). Brown states that the simplest explanation of the footwashing is that Peter’s questioning ‘enabled Jesus to explain the salvific necessity of his death: it would bring men their heritage with him and cleanse them of sin’.[41]

The cleansing provided by the footwashing in 13:8, 10 is paralleled in 15:3 by a cleansing through Jesus’ word. This leads Bultmann to hold that the former is symbolic of the latter.[42] However, Thomas shows the problems this view faces in light of the two very different contexts in chapters 13 and 15. He follows the analysis of C. H. Dodd who draws attention to other paradoxes in John where eternal life comes by eating the Son of Man’s flesh and blood and yet also by the words Jesus speaks.[43] This points to a close unity, rather than dichotomy, between the word of Jesus and the service of Jesus, such that the word which Jesus speaks is actually his explanation of himself and his work: the two are inseparable.[44]

We do not suggest that John 13:1-11 provides a comprehensive interpretation of the cross, but rather that it offers some material which would need to be incorporated into an overall presentation. The passage connects with at least two wider issues. First, it has been beyond our scope to explain exactly how the cross cleanses and the precise ways in which this might be attached to terminology of sin and atonement. But the washing terminology of chapter 13 may provide hermeneutical contact points for other parts of the Gospel which could shed further light on how Jesus’ death cleanses.[45] Second, Barrett wants to stress that although hyper carries sacrificial connotations in John, ‘no precision about the mode or significance of the sacrifice can be obtained’.[46] Yet at the same time he asserts: ‘the cleansing of the disciples’ feet represents their cleansing from sin in the sacrificial blood of Christ’.[47] In our view Barrett has gone further than he intends to in showing how, at the very least, the hyper sayings might potentially engage in a dialogue with his interpretation of the footwashing.[48]

Our acts of humble service may make us like Jesus, but it is only Jesus’ act of humble service that makes us belong to him.

Regardless, our discussion has aimed to show that a broader methodological approach to interpreting the cross will not so much completely reject the critical consensus as simply aim to qualify it. John 13:1-11 is one possible indicator that Jesus’ death could be interpreted as a glorious return to the Father through the humiliation of the cleansing cross. Such an interpretation has important homiletical consequences. While we may (rightly) not be tempted to preach the importance of copying the physical act of footwashing, it is surely much more common - on the basis of 13:15 - to see in the passage the purely exemplary, and to not realise that the ongoing mandate to abase ourselves and humbly serve one another is based on the once-for-all ‘complete demonstration of Jesus’ love, which is symbolized by Jesus’ lowering himself to the status of a slave in the footwashing and realized in his vicarious cross-death’.[49] Our acts of humble service may make us like Jesus, but it is only Jesus’ act of humble service that makes us belong to him (13:8).