A Force for Good: William Wilberforce and the end of slavery

A Force for Good: William Wilberforce and the end of slavery

Ermine Desmond

Come back with me, to the year 1780, to Hull, where a lavish feast is being held to celebrate the coming of age of William Wilberforce. Men and women are dancing in the street and getting drunk and an ox is being roasted whole. William, having inherited his father's wealth, has decided to enter politics so the feast is lavish, also, in order to secure the votes of the landowners of Hull. William would spend about £8,000 in bribes that summer but when he was elected with a huge majority, the cost of the bribes, the feast and the ox would be counted as, “money well spent".

After his father's death, when he was nine, he had been sent to stay with his rich uncle and Aunt in Wimbledon - they were fervent evangelicals. There, William met the jolly John Newton who had once been enslaved in Africa and later, after he had become a Christian, the captain of a slave trading ship. William revered him as a parent (some of you will know Newton's hymns: "Glorious things of thee are spoken", "Amazing Grace", “How sweet the name of Jesus sounds" etc.). William’s mother, although a strict churchgoer herself, feared he might become an evangelical, so she took a coach and fetched William away. "I was so much attached to them, I was almost broken hearted," he said. She was nearly too late for William had begun to imbibe their views.

"William’s mother, although a strict churchgoer herself, feared he might become an evangelical..."

After some years at a Grammar School, (where an usher, Isaac Milner, the son of a poor weaver, served) William went up to St John’s College Cambridge. There, he did little work; his tutor, he said, "never urged me to attend lectures and I never did". Relying on his love of the classics and ready mind to pass examinations, he felt that had he worked he would have done far better than most. It was a lifestyle he would later bitterly regret.

Having, by now, inherited his uncle's money also, he left Cambridge a very wealthy young man. The charming, witty, entertaining Wilberforce, with the most wonderful speaking and singing voice, readily entered into the cheerful, social life of Hull: playing cards, attending the theatre, dining, with excellent food and wine. He began to think that the beliefs of his uncle and aunt had been those of vulgar or at least uneducated persons. However, men detected an underlying seriousness about him. One, designating Wilberforce as a trustee of his will, said, "I thank the gods that I live in the age of Wilberforce and that I know one man …. who is both moral and entertaining."

Wilberforce took his seat in the House of Commons just three months before his dearest friend the brilliant William Pitt. Wilberforce lived in what had been his uncle's house in Wimbledon. A house that was demolished as recently as 1958 despite its having been Wilberforce's; having a staircase decorated by Angelica Kaufman and a room where Pitt always slept. "We will be with you before curfew and expect an early meal with fresh peas and strawberries," Pitt had written in a note.

It was essential then for a rich young man to join the clubs of St. James’s, so Wilberforce belonged to the prestigious White’s, to Brookes’ for gambling, to Boodle’s and Goosetrees’ for dining and conversation. He attended the theatre (seeing Mrs. Siddons and Kemble act in Hamlet) the Opera, the pleasure gardens of Vauxhall and spent happy days at the races watching his own horse run.

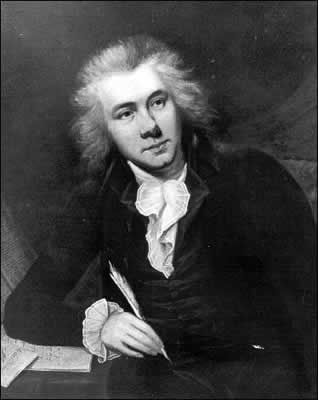

The only fly in the ointment was his poor health. Always undersized - about five foot three or four - "an ugly little fellow with a long tipped-up nose - too long for his face” (his portraits would always be painted full-face in order to disguise it). Once, when he was ill, the doctors said, "that little fellow with his calico guts," "would not last a fortnight." Debility, loss of appetite, feverishness and recurrent diarrhoea would now suggest ulcerative colitis. Not enough is known about his eyesight to make a diagnosis but it was so bad, "that I can scarce see how to direct my pen”; it frequently stopped his reading altogether.

At some point, he was prescribed opium, then, possibly, the best available treatment but over time, it may have caused him to become more untidy, more indolent and absent-minded. The worst effects of which was that his careless and haphazard method of doing business made him unfit for important positions in government (not even when Pitt was Prime Minister did he ever hold office).

"his careless and haphazard method of doing business made him unfit for important positions in government"

During the long summer vacation, Wilberforce liked to go to the Lake District - the “Paradise of England” he called it - where troupes of friends, “just passing through,” visited him, so preventing the solitude become boring. Then, he liked to travel on the continent with Pitt or others. Once, he took the brilliant Isaac Milner, across whose papers the examiners had written, “Incomparabilis” and who was now lecturing at Queen's College Cambridge and seemed a lively, dashing young man of the world. They argued about an evangelical friend who for William's taste, "took things too far". Milner defended him. William asked Milner’s opinion of a book he had casually taken up: Philip Dodderidge’s “The rise and Progress of Religion in the Soul” (some of you will know his hymns: "O God of Bethel," "Hark the Glad Sound the Saviour Comes," and "O Happy Day that fixed my choice on thee my Saviour and my God"). “One of the best books ever written,” was Milner's reply. Wilberforce now experienced Milner's incisive mind arguing in defence of evangelical Christianity - he was formidable.

By the time they reached England, William was convinced of the intellectual truth of the gospel but thrust it to the back of his mind and resumed his cheerful, social and political life. During the next year’s travels they discussed the New Testament in the original Greek and slowly, intellectual assent began to change into a profound conviction that he was a sinner and so needed a Saviour. He began to sicken at the selfish lives of the rich with their overeating while the poor starved. This slow change eventually caused him to rise early to pray. For some months, he was in anguish but kept out of company lest his friends should find out. He was terrified that he would lose his popularity and that he would have to give up politics.

Feeling that he was going mad, he sought out John Newton who did not disappoint – he calmed him and advised against withdrawing from politics. “It is hoped and believed,” he would later write, “that the Lord has raised you up for the good of the nation.” It must be stressed that few other evangelicals would have then taken this view. Wilberforce's heart was lightened and, down at Pitt’s house, he went into the fields and amid the early birdsong he gave thanks to his Saviour for his salvation.

"He began to sicken at the selfish lives of the rich with their overeating while the poor starved."

His mother supposed that he had gone mad but when they were next together, she noticed a complete absence of his old irritable temper. A childhood friend remarked, "If this be madness, I hope that he will bite us all!"

With his awareness of God's grace, went a desire, “for the strictness and purity of the Christian character.” Therefore, Wilberforce began to read widely becoming better read than most MPs. He sold his racehorse; gave up all five clubs; stopped eating huge meals; limited himself to six glasses of wine rather than the three bottles then the norm. He and Isaac decided to criticise and then fine each other for lapses in behaviour. William soon found that Isaac did most of the criticising and he most of the paying and so gave that idea up.

William, too, longed for his friends, especially Pitt, to know this salvation through Christ’s death and resurrection but Pitt, as far as we know, never did. His brilliance meant he was both Chancellor of the Exchequer and then Prime Minister in his twenty-fourth year. Pitt’s old tutor, Bishop Pretyman, disliking Wilberforce's evangelicalism, did his best to keep them apart when Pitt was dying.

William’s growing Christian awareness affected not only his private but his public life - "a man who acts from the principles I profess," he said, "reflects that he is to give an account of his political conduct at the judgment seat of Christ." He had, almost always, voted with Pitt but now, he voted guided by his conscience. On one such occasion, his vote helped make Sir Charles Middleton, (another evangelical) Lord of the Admiralty. Sir Charles reorganised the navy's supply lines and ordered new ships so enabling Nelson, with whom he got on very well, to win the Battle of Trafalgar. This meant that Britain ruled the waves for many years. Wilberforce was becoming what was then an unknown phenomenon - an independent.

He began to support unpopular causes. On a picnic to see the Cheddar Gorge, he was so appalled by the conditions of the poor he passed that he returned, picnic uneaten, to organise food, clothing and schools for the poor for which he paid. The farmers grumbled, "We shan't have a boy to plough or a wench to dress a shoulder of mutton." As a governor of Bart's, he found that medicines were sold privately and illicitly for profit. He supported charity schools and the Sunday School movement; he helped found the British and Foreign Bible Society - all helping make the poor literate - the RSPCA; the National Gallery; the Trustee Savings Bank; and the British Institution for applying science to everyday life, enabling, for example, Humphrey Davy to invent the miners’ lamp. In all, Wilberforce led or supported sixty-nine societies - his influence was always powerful.

He made mistakes, of course, like failing to see that workers would need Trades Unions to represent them before the powerful mill owners.

Of all the good causes that Wilberforce embraced, the nearest to his heart was the abolition of the slave trade and then slavery itself. Friends, like Sir Charles Middleton, who had been in the West Indies, were sickened by the horrendous treatment of the slaves. It was Lady Middleton who said to her husband, "I think you ought to bring the subject up before Parliament." He felt he was not the man to do it. Who could they ask? Wilberforce of course. Pitt too had urged him to take up the slaves’ cause. (The stump of the tree under which they had sat is still there apparently - with a plaque). After he had researched the conditions of the slave trade, particularly of the Middle Passage, Wilberforce said, "So dreadful, so irremediable did its wickedness appear that my own mind was completely made up for abolition, let the consequences be what they would." One consequence was that, at one point, he would fear for his life. The merchants warned him that abolition would mean ruin for Britain.

"The merchants warned him that abolition would mean ruin for Britain."

There were always diversions brought up to forestall his doing anything. Cobbett asked, "Was the state of the slaves any worse than the labourers paid a pittance in England?" Wilberforce knew that they were: one in every seven slaves died during the Middle Passage because of overcrowding, no hygiene, inadequate food and lack of exercise; the women were raped constantly; on arrival, they wore spiked shackles on their ankles, neck irons and were flogged mercilessly - not infrequently, this all terminated in murder. As Africans were the only people who could withstand the West Indian climate, slaves were in high demand; "A fine man slave …. is worth near double it was formerly," Newton had written. Note that he called the slave, ‘it.’

At first, Wilberforce, as he warned the House that he was about to move the Abolition of the Slave Trade, was quite optimistic: "As to our probability of success, I assure you, I entertain no doubt of it". But, soon, his other causes began to crush him. One was, ‘The Reformation of Manners in England’; they laughed in his face saying, "… in a wealthy nation such debauchery and lack of religion was what was to be expected. He began to dread this fight against slavery which would lose him friends - even Pitt would cool but to carry abolition would be better, he felt, than to be Prime Minister. It is thought that at this time he suffered a nervous breakdown. I love one of his prayers: "Lord, I am in great troubles, insurmountable by me, but to thee slight and inconsiderable. Look upon me with compassion and mercy…."

May 1789 A debate - frail, reduced but cheerful, Wilberforce rose; he spoke for three and a half hours. He had written only a simple speech, numbering his points (that piece of paper is now in the Bodleian Library in Oxford). Many said, he equalled anything that had been uttered even by Demosthenes. "I and the whole Parliament are guilty …. for having suffered this horrid trade to be carried on …. we are all guilty." To the plea for providing better conditions slowly, he said, "It is not mere palliatives that can cure this enormous evil: total abolition is the only possible cure for it … we cannot turn aside." But the Commons did turn aside - Wilberforce lost - he knew that the slaves would continue to suffer.

April 1791 A second debate was held. Wilberforce spoke for four hours. "Whatever the outcome,” he said, “I have attached my happiness to their cause and shall never relinquish it."

Wilberforce lost by 75 votes.

April 1792. A third debate; it looked hopeful but an amendment was brought forward that the trade be abolished gradually, in fact in three years eight months. Wilberforce thought of the slaves’ suffering - he had lost again.

Early in 1793 he tried again - he lost by eight votes.

Later, in May 1793 he tried to prohibit British ships from carrying slaves. He was told to get a hairdresser to curl his straight locks; to find a woman; to visit the theatre because his brain had become addled.

February 1794. He tried again; the Commons passed it - the Lord's did not - people began to ostracize him.

Easter 1796. He tried again, losing by four votes.

Then William fell in love with, and married, the beautiful Barbara Spooner, an evangelical like him but eighteen years younger (38 - 20). He remained in love to the end - always signing himself "Thy Wilbur." To him, she seems to have been perfection but friends said, "you would never know how much of the angel there was in Wilberforce unless you had watched his patience with his wife." The many guests, bidden or unbidden, found very little to eat at breakfast (although she saw that Wilberforce's plate was always full). The servants, none of whom Wilberforce could bring himself to pension off, did more or less as they liked.

1804 Another debate - it passed the Commons but the Lords shelved it for a year. In defeat after defeat Wilberforce came to realise that, "When men are devoid of religion, I see that they are not to be relied on."

"When men are devoid of religion, I see that they are not to be relied on..."

In October 1805, Nelson won Trafalgar and in 1806, Pitt died - these events transformed Wilberforce's task. A brilliant lawyer, James Stevens, then suggested they try to give British ships power to search any ship suspected of carrying slaves even if it were flying a neutral or friendly flag. This passed by 22 votes (2nd May 1806)

February 1807 - another debate! Wilberforce won by 267 votes. The house rose to its feet and turning towards Wilberforce cheered him wildly - he sat with tears streaming down his face. No more Africans would endure the Middle Passage (in fact it took many years before it could be fully enforced). The slaves, “wished the best of blessings on massa Wilberforce's head.”

John Newton, near death, rejoiced to hear the wonderful news.

Now, Wilberforce set out to abolish slavery itself. He attacked the theory that black people were degraded - slavery degraded both them and their white masters. He was offered a place in the Lords, he refused. Someone, cunningly suggested the slaves be made apprentices: he objected - he knew their conditions would not improve.

By now, he was very, very thin, like a soul almost without a body. He became very ill: he loved Paul’s words in Philippians; "Do not be anxious in anything."

Then, 26th July 1833, a Bill to abolish slavery passed the Commons then the Lords. England paid £20 million to purchase the slaves’ freedom. He could not be there but said, "I thank God that I have lived to witness it."

He began to sink. Three days later he died. He was 74. The government asked that he be buried in Westminster Abbey; his coffin was carried by two Royal Dukes, the Lord Chancellor, the Speaker and four Peers. Members of both Houses followed it.

Wilberforce - a force for good - had entered into the joy of his Lord.